By Marc Myers at JazzWax

The year 1969 was a busy one for pianist Bill Evans. In January and March, Evans with bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Marty Morell recorded What's New with flutist Jeremy Steig. In February, the trio was recorded furtively at New York's Village Vanguard (The Secret Sessions). Then they moved on to Holland in March (Live In Hilversum 1969) and Italy in July (Autumn Leaves). Back in New York in early November, Evans began recording From Left to Right, his moody Fender Rhodes-acoustic piano album backed by an orchestra. Later that month, the trio recorded live in Copenhagen (Jazzhouse) and Amsterdam (Quiet Now).

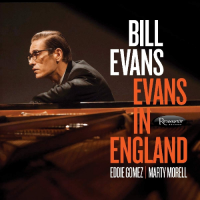

Finally, on December 1, the Bill Evans Trio opened at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in London, a run that would last until December 27. At various points during the month, the gig was beautifully recorded. The music captured Bill at his gentle and poetic best, a throwback to his playing of several years earlier. The recording has just been released on Evans in England (Resonance). Like the Wes Montgomery set that I reviewed yesterday, this two-CD set with a 36- page booklet of liner notes and interviews was produced by Zev Feldman.

According to Zev's introductory essay, the tapes were in the possession of a friend of Leon Terjanian, a resident of Strasbourg, France, who is among the world's many “trench coat" tape collectors. These fans own rare and previously unreleased recordings of major artists and trade them among each other. Zev traveled to Strasbourg twice to meet with Terjanian and to hear the tapes, research them and negotiate for their release. Terjanian would befriend Evans and film him in Lyon in 1978, using footage in his film, Turn Out the Stars, which was screened just once at the Montreal Jazz Festival in 1981.

As Zev was preparing Evans in England, he reached out to me for the album's main liner notes. To ensure that Evans was actually at Ronnie Scott's in December 1969, I called the club in London to verify the dates. They weren't sure, since their records were incomplete. So I went off to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at Lincoln Center, one of the finest arts research facilities in the city.

After an hour on the microfilm projector scrolling through the 1969 Melody Maker, the British music tabloid that published from 1926 to 2000, I found ads for the Bill Evans Trio at Ronnie Scott's throughout December.

For the notes, I also interviewed Marty Morell, my favorite Bill Evans drummer. I love Marty's delicate but determined touch and how he plays in and around Evans. After listening to the tapes, Marty said, he was certain the music was recorded in December 1969. During that visit to London, Marty recalled, he agreed to endorse Paiste cymbals, a Swiss company. Midway through the Ronnie Scott's run, he said, he switched out his Zildjian cymbal for a Paiste “Free Ride"—a cymbal without a bell.The model let him ride the cymbal without overshadowing Evans's playing, something that Evans's mother had groused about months earlier in Washington, D.C.

The final mind-blower that emerged from my research for these notes was the origin of Elsa. Composed by Earl Zindars, the song was an Evans favorite and appears on numerous Evans albums over the years. The list includes Explorations, Trio '65, Paris 1965, Momentum, Live in Paris 1972, Re: Person I Knew, among others.

Despite going through the liner notes of these albums and thumbing through books, no one ever bothered to look into why Earl Zindars named the song Elsa. Who was this woman? I called Anne Zindars, the late composer's wife. Here's what she told me: “After Earl wrote the song, I asked him, 'So, who's Elsa?' Turns out the song was named for the lioness, Elsa, in the 1960 book, Born Free, which became a movie in '66. Earl loved the book when it came out."

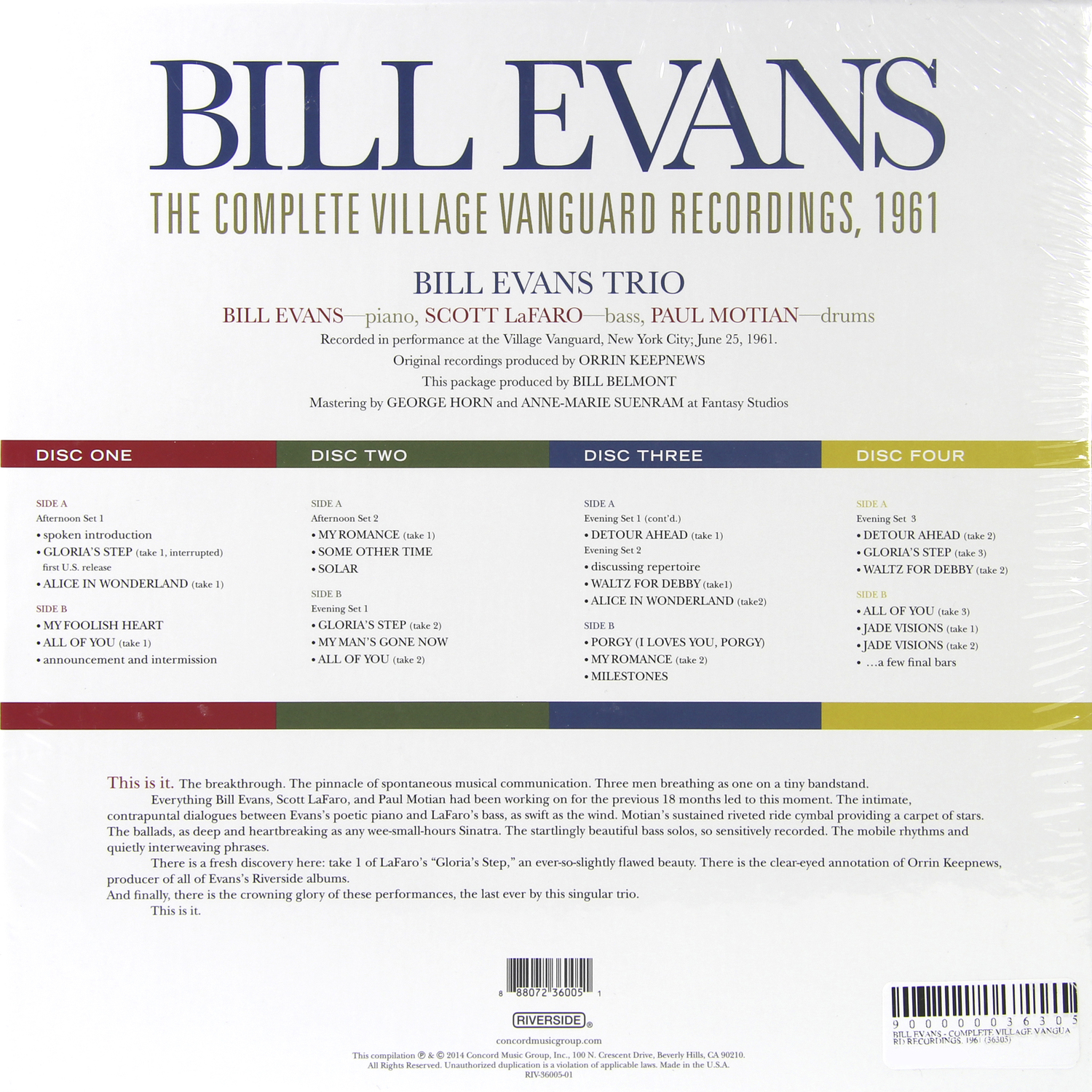

I think you'll find that Evans in England is the finest live recording by this trio and easily in the top five by Evans in general. For me, it's bested only by Sunday at the Vangaurd/Waltz for Debbie recorded in 1961 and Bill Evans at Town Hall in 1966. As you'll hear, the music in London is alive and spry without Evans's keyboard agitation or complaint. All 18 tracks feature Evans at ease; Gomez conversational, not nagging; and Morell on sticks and brushes egging Evans along. We're lucky that such artistic grace surfaced and that Resonance producers Zev Feldman and George Klabin had the wisdom and determination to put the music out.

Bill Evans died in September 1980.