By Claudio Botelho

I really hate them. But, from time to time, I come across one when, without hesitation, I find listenable from start to finish. As a rule, CD1 differs from CD2, being one much worse than the other: too much blank space to be filled and this asks for much inspiration. Well, we don’t find inspiration stored in grocery stores… (Just a brief digression: the double vinyl I’d spent the most time listening in all my life was, UNDOUBTLY, Ahmad Jamal’s “Digital Works”, recorded in the eighties. It has became a single CD, but, irrespective of doubling matters, it was my most all time listened album. Listen, to check, his rendering of “A Time for Love” and learn how to fiery improvise a tune WITHOUT ever getting far away from it! Jamal is in the wings and will be spotted soon. I’m just waiting to receive his latest – “Blue Moon” – which comes highly recommended).

A fortnight ago, I wrote about one of my jazz heroes. His name is Eddie Gomez, he plays the acoustic bass and, for my personal amusement as a jazz lover, nothing tastes better.

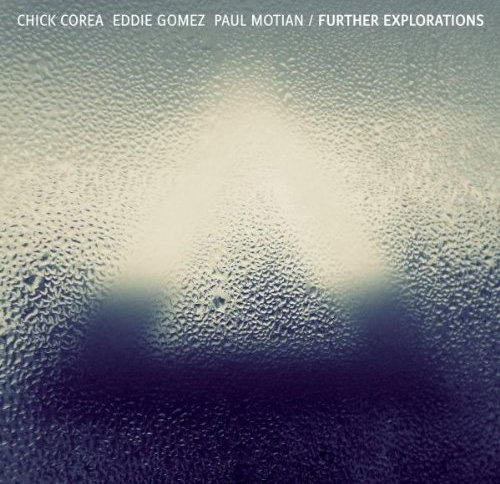

In my writing, I said I was longing for a new double CD of a project he was part of, along with ChicK Corea and the recently deceased great drummer Paul Motian; this one another one-of-a-kind musician. I was salivating while waiting to put my hands on their “Further Explorations”…

So, contrary to my beliefs, these two CD’s would be very welcome this time and I was anticipating the great pleasure I would have to listen to the conjunction of these three musical icons of jazz. Gomez, certainly, would deliver his utmost, as this work was about Bill Evans and this, alone, would bring inspiration enough to fill more than two and a half hours of CD playing.

Besides, I would have, numerically, two thirds of an Evans trio, although lacking its head and main inspiration. Instead, I’d have Corea…

Granted, Corea is not Evans and one may ask if there are two more dissimilar pianists. Surely the answer is positive, but they DO are different from each other, aren’t they? If I were asked to summarize each in one word I’d call the first one “passionate” and the latter “lyrical”. They aren’t pieces of the same cloth, indeed!

Anyway, I would have, again, “Peri’s Scope”, Gloria’s Step”, “Laurie”, “ Turn Out the Stars”, “Very Early” and thirteen others which were performed throughout a ten days stint at Blue Note, in New York. Instigating would be to listen, for the first time ever, to an Evans theme named “Song nº1”(probably a provisory name, at the time of its composition, I gather), as much as seeing two former Bill Evans partners playing together.

Well, well, well… I hate double CDs, but this time, from the outset, I tell you: on that Friday night, I listened to it for some four hours in a row! Was I in front of something really outstanding, something never to forget about? Not really; there was some unevenness throughout the presentation. At times, Corea and Gomez seemed a bit strange to each other… I have a hunch Gomez more intricate lines had something to do with this. Besides, Corea is not exactly a sparse playing dude… Some overload of good intentions here! Two corps cannot occupy the same space at the same time, you know…

Motian, as usual: most of the time rounding off things with his cymbal playing, usually changing to a combination with strong drum whacks on solos. He, like Gomez, plays like anyone else. Those not acquainted with him, on first listening, may be misguided into thinking he’s playing at random. No, no, man, listen better!

Anyway, a bit more rehearsals would have helped the interplay, but this was a once-in-a-life adventure whose raison d’être was to honor Bill Evans, and, as it was, the objective was fulfilled.

On listening to some tunes, many times, tears came to my eyes, especially on the renderings of Evans songs. In particular, I was especially touched when tried “Laurie”, “Turn Out the Stars” and even the joyful “Peri’s Scope” and, now, a surprise: the hitherto recorded “Song n.º 1” which, on account of this, became a paradigmatic presentation. Corea was never so “Un-Corea” before. (just to be different from Mr. Chris Cooley, who, in his evaluation of this outing in his Amazon review, referred to Corea’s presentation as “Un-Chick”). For this, he abandoned his usually latin-flavored style to better suit the spirit of the song. For my money, this song is the highlight of the project.

Of course, in my case, there was a mix of feelings: I listened to all these songs by the time they were first recorded by Evans himself and had followed his career ever since, until his disastrous and untimely death. As much as I don’t want to admit, nostalgia has been playing an important role here: I was back at my early teens again. This experience has brought about many fond memories of so much delightful jazz musical sessions of my youth and, of course, Evans – the man who lived and died for his music – was the greatest hero, then.

But, in general, I don’t nurture nostalgia, as it is a kind of a denial of the present. When we get older, it is plain natural to become addicted to some habits which, sometimes, takes us a bit away from modern practices. I strongly strive not to be trapped by this. I try to lead my life as anyone else, although having much more certainties in my head and heart than before. But this is surely a good thing in getting older.

As I said, I try very hard to be up-to-date, but am I successful? I don’t know…

All told, I think you’d better read other reviews of this CD, as this effort of mine probably conjures some biasing. Or, try it for yourselves…

Meanwhile, I keep on hating double CD’s.